August 13, 2003

Letting it Roll -

Benjamin Tosi Hopes to Expose Bocce to a New Generation of Players

By John Branch

SAN FRANCISCO --

Tucked under a corrugated roof, next to a concrete shack with a priceless view,

gray-haired men roll and toss balls back and forth on a clay court, just as they

have done for decades.

The men, and sometimes a few women, gather at the Aquatic Park Bocce Club

every afternoon at 1. Most either speak Italian or have the accent of someone who

learned English as a second language.

Tourists often stumble into the scene, stopping long enough to absorb some

neighborhood culture or take a picture before turning back toward San Francisco

Bay or rejoining the masses at Ghirardelli Square.

Benjamin Tosi stumbled into this world, too, a few years ago. But the Fresno native

never left. Now he is rolling and tossing balls back and forth, five times a week, like

men nearly three times his age.

The game is what they have in common. That's about it.

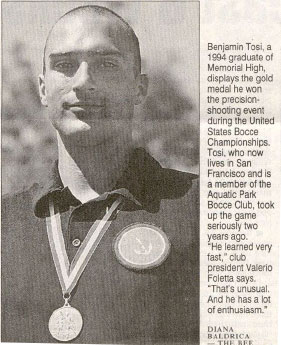

Tosi, a 1994 Memorial High graduate, is only 27, the club's youngest member.

He is lean and muscular. He moves at a hurried pace, not with the leisurely, retired

rhythm of the others. The only Italian he speaks is "bocce Italian."

He got serious about playing two years ago. He ordered his first set of brass bocce

balls 13 months ago.

And he is a national champion.

Tosi won the precision-shooting event at June's Bocce National Championships

in Highwood, Ill. He is part of a four-member American team headed to Nice, France,

for the World Volo Bocce Championships in October.

"He learned very fast," club president Valerio Foletta says. "That'sunusual.

And he has a lot of enthusiasm."

And Tosi is bringing that enthusiasm to the ancient -- and aging -- world of bocce.

Ready or not.

"I'm trying to break the stigma that this is an old, retired man's sport," says Tosi,

who spends the other half of his awake time as manager of events for the University

of San Francisco, his alma mater. "Because that's only here in this country."

On the front of his American gold medal is a raised relief of a bocce player in action.

The man has a visible gut hanging over his belt. And a receding hairline.

"It's funny, but it's cool," Tosi says.

It's also indicative. The Aquatic Park club had seven courts and 120

members about 25 years ago, Foletta says. When Tosi arrived, it had two

courts and 30 members. So Tosi, named the club's secretary in January, is recruiting

more young members willing to part with $20 a year -- "A steal, if you askme," Tosi says.

About 10 have joined. The club rebuilt a third court, made of layers of compact

dirt and clay and pulverized oyster shells.

Tosi, fast-talking and energetic, has a showman's streak, an ad man's flair. He wrote

a blurb about his national title and sent it to Sports Illustrated. The magazine called

the next day, sent a photographer, and Tosi appeared in "Faces in the Crowd" a

couple of weeks ago.

"My desire is to do well in the world tournament, so Americans can get enthusiastic

about it," Tosi says. He understands the odds are against world success.

No American has won a world title, according to Marco Cuneo. His late father, Juanito,

was a nine-time national champion from San Francisco .

Marco Cuneo, 30, qualified for the national team for the fourth time. He is Tosi's

mentor and primary playing partner, a fellow Gen-Xer who befriended Tosi most

when Tosi began hanging around the club between shifts as a valet at a restaurant

around the corner.

"I guess he saw potential," Tosi says. "And, more than anything, a willingness to learn."

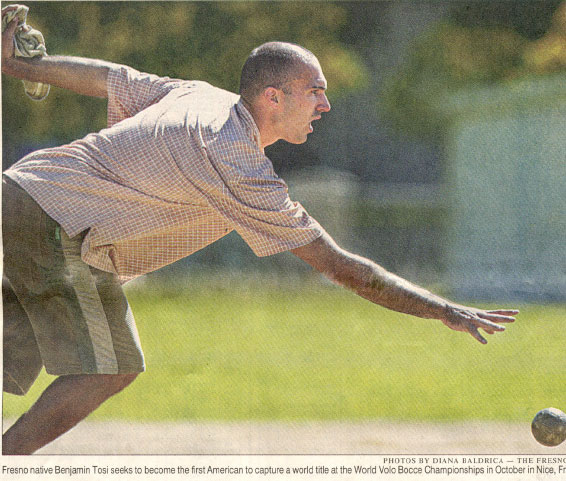

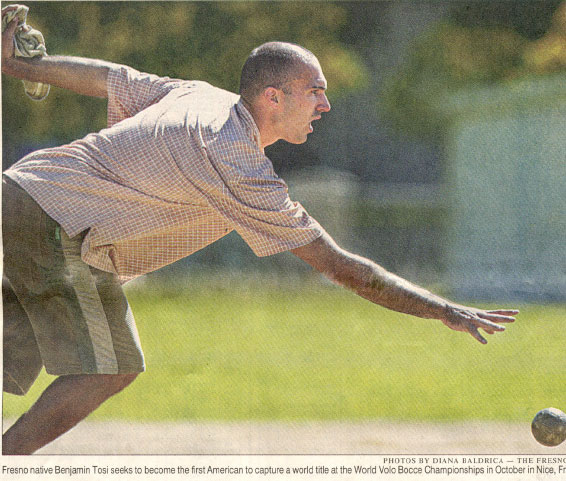

Get beer-in-one-hand lawn bowling out of your mind. While bocce centers on getting

balls closer to a target than the closest ball of the opponent, Tosi and Cuneo play "volo,"

a highbrow variation steeped in history.

It is played with brass balls about the size of softballs and weighing 2 pounds or more,

each carved with distinctive, extravagant patterns. Tosi just bought his third set; the balls

cost about $60 each.

Most of the shots aren't bowled at all but thrown underhand 50 feet or more in an attempt

to knock an opponents' ball from the target.

On this sunny day, Tosi plays a merry man named Carlo, who deftly rolls his first ball

down the length of the court. It stops an inch from the target.

Tosi holds a ball in his right hand, concentrating on the far end of the court.

He takes eight increasingly quick steps toward the throwing line, then half-leaps and

launches the brass ball in a high arc. It is an odd motion -- part bowling and part ballet,

like a running softball pitch -- unique to bocce.

His ball crashes into the target on the fly, sending Carlo's ball off the court.

"I can do it every once in a while," Tosi says with a smile.

"That's what I love about this game. You have this delicate, sweet-and-innocent rolling

part, and then the throwing, with this thunderous crack of the balls colliding.

It's two extremes. Kind of fits my personality."

The question is whether bocce is ready for that personality. Even the club members

weren't sure what to make of Tosi at first. The guy just kept coming around, watching

their games for hours at a time, grabbing some balls and tirelessly practicing by himself.

It took several months before members invited him to join one of their contests.

"It's kind of a hard group to crack at first," Tosi says.

Now Tosi talks of improving the national organization, of attracting the world

championships to the United States for the first time, of getting bocce into the

Olympics.

If nothing else, maybe the national medals will be redesigned, the model given some

hair plugs and a Bowflex machine.

Or maybe, just maybe, they'll eventually put Tosi's likeness on the medal instead.